Manila was a hub for international trade in the 19th century, and it was open to all international shipping without restrictions. Foreign firms opened offices in Manila, and many foreign merchants lived here.

Smuggled goods were a big problem as foreign traders would avoid customs duties and taxes in Manila by shipping their goods to other Philippine islands and sneaking them into Manila through local ships making interisland trips.

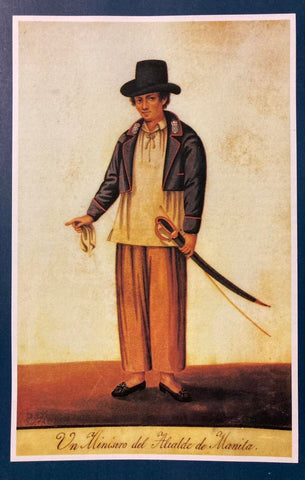

The Customs House guards were tasked with monitoring and catching smugglers. The man in the painting here is a customs officer according to Nick Joaquin, author of Nineteenth Century Manila: the World of Damián Domingo (1990).

In Domingo’s Baboom collection of tipos del pais (types of the country, native dress) paintings, No. 3 (1833), he included this piece above titled Un Ministro del Alcalde de Manila, which literally translates to “A Minister of the Mayor of Manila”. Customs officers were usually appointed by the mayor, and their authority was signaled by their baton and sword, which this man carries in his left hand. Our description of Domingo and the Baboom collection is in our previous installment 18.1.

Customs officers were another part of the principalia class of elite native or mestizo municipal leaders working for the Spanish government. As other principales (members of this class), customs officers dressed much the same. This man wears a Barong Tagalog with a string tie and a short jacket over it, called a Camelot, a privilege granted to principales by Spanish edict.

Per Joaquin, the light brown wide leg trousers worn here are made of imported English cotton (transported to the Philippines via the Galleon Trade) and tailored locally. Handkerchiefs were apparently always kept in the hand and not in the pocket. The officer here also wears slippers on his feet and his European style hat is a cousin of the bowler hat.